The Dead from the Kirschbaum Cave:

Three Burials, Three Millennia

The Kirschbaum Cave in the Franconian Alb was discovered in 2010 by speleologists, members of the exploration group Fränkischer Karst e.V. The bone finds made at this occasion were left untouched by the researchers, allowing this cave – named after a cherry tree which at the time marked the entrance (kirschbaum=cherry tree, in German) – to become the first chamber-cave in Germany which, having been discovered in its original state, is now being investigated by the means of the most advanced techniques available, by archaeologists of the University of Bamberg.

Neolithic men and dogs

As soon as it was discovered, the Kirschbaum Cave confronted archaeologists with a puzzle: the skeletons of Celts found inside dated back to a time, 500 BC, when Celts did not normally bury the dead in caves. Now, with new results back from the lab, even greater questions are raised.

For the Celts were not by any means the oldest dead in the rock crevice. 2000 years earlier, it was used once as a burial site for humans and animals. What made the Kirschbaum Cave so attractive a place to release bodies into the depth of earth?

The remains of at least seven humans are resting in the narrow karstic cave. Five of the dead were adults, two were adolescents. They are accompanied by nine domestic animals, three wild animals, rodents, in addition to some 30 additional, not identifiable bone fragments.

Yet they originate in three wholly different epochs. “Most likely, there exist no relationship between the dead from the Iron Age, those of the Bronze Age and those of the Neolithic,” explains the chief excavator from the Department of Early Archaeology of the University of Bamberg, Timo Seregély. “Prehistoric men discovered this cave every time anew.”

The first time occurred between 2910 and 2660 BC – at least according to what is known so far. "We are far from having reached the bottom of the cave,” remarks Seregély. "Many areas are filled with rubble and sediments – we don’t know what’s awaiting us in these deeper layers."

Two humans, who at the end of the Neolithic found their last resting place in the Kirschbaum Cave, belonged to the Corded Ware ceramic culture. They weren’t there alone: around them lie the remains of three dogs, three pieces of cattle and at least one pig.

"But the cattle didn’t die in the cave,” the scientists conclude from the examination of the bones. “They were chopped into pieces before.” This could not have been done inside the cave itself: it is so narrow that the dead themselves could probably not have been carried inside, but rather they were merely pushed through the entrance cleft, then the skeleton remains migrated over time into the nether regions of the cave.

A Bronze Age Woman and a Red Deer

More than half a millennium passed after the Corded Ware people gave their dead to the cave. Then, in the Early Bronze Age, some time between ca 1980 and 1740 BC, new people found that this karstic cave was decidedly an ideal place to deposit humans and animals after their demise. Skeletal remains of a woman and a red deer belong to this period. “A deer bone lay directly next to her skull,” describes Seregély what he found there.

Celts buried as they shouldn't be

Again another millennium passed, until finally in the Iron Age, between 760 and 400 BC, the Celts arrived. They lay into the cave two adolescents and an additional adult – as well as a sheep. Why they would have done this remains a mystery. For normally the early Celts of this region buried their dead under artificially piled-up earth mounds or barrows – but not in rock crevices.

Additionally to the first datings, the results of isotope analysis have also come back from the lab. Seregély had the bones tested for various isotopes of carbon and nitrogen. So that one can make out, for instance, what had been the diet of the dead.

"With the Corded Ware people, the 15N-values were relatively high," he explains. "This means they ate a higher share of animal proteins, that is meat and milk.” The Celts were different: "In comparison with the Corded Ware people, they had significantly lower 15N-values, therefore they must have nourished themselves rather with food of vegetal origin."

High-Tech Excavating

A 3-D-scanner used in the excavation

Step by step, Seregély tries to solve the puzzle of the Kirschbaum Cave: "The great question is: what went on here?” How did the dead humans and animals get into this narrow rock crevice? Were the dead of the same epoch possibly related? Did fire play a role in the depositions?

In order to clear these questions, Seregély and his collaborators are working with the utmost care. They enter the cave only in protective suits, with gloves and masks – so as not to contaminate the bones with their own DNA.

Before anything was recovered, the archaeologists captured the cave structure, and the first layer of bones with the help of a high-precision 3-D-Scanner. A Stereo-3-D-scanner was also used to document to find.

The smallest alterations on the bones can in this way be captured in the minutest detail in 3-D-pictures and in the original color: even traces of cuts or of singeing become visible.” "In these area of dolomite formations, in which the Kirschbaum Cave is situated, there exist a great many caves, which were used for body rituals,” says Seregély to justify his prudence, “but they have been badly investigated.”

In the first half of the 20th century, when most of them were excavated, 3-D-scanners and DNA analyses were still far in the future. “This time around we have the opportunity, thanks to these technical possibilities, to do a lot of things a lot better.”

To begin with, with all the help of the natural science at disposal, the old bone remains and the sediments still present in the cave must surrender all informations which they can possibly yield. What exactly happened down there at what time? Then there is the context: Were there other graves in the immediate vicinity? And where did the people live, before they died?

“Only when we are in possession of this knowledge, will we be able to slowly attempt to approach the central question of the “why?” concludes Seregély. "But until we get to that point, there’s still a long and arduous way ahead. "

Angelika Franz

translated and adapted by Anne-Marie de Grazia

Der Spiegel: original article in German

Timo Seregély (left) and members of the excavation team Andres Schaefer, Gerhard Gresik

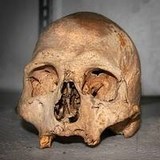

Skull of a man - First half of the Third Millennium BC

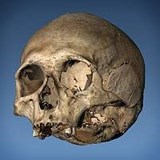

Skull of a man - between 8th and 5th Century BC