Neanderthal News - 2020 - Part IV: Women and children

- Researchers Sequence Mitochondrial Genome of 80,000-Year-Old European Neanderthal

- Researchers Sequence Genome of Neanderthal Woman from Chagyrskaya Cave

- Women with Neanderthal Progesterone Gene Have Higher Fertility

- New Research sheds light on weaning of Neanderthals

- Neanderthals’ Deep and Short Ribcage was Already Present at Birth

- See also:

Researchers Sequence Mitochondrial Genome of 80,000-Year-Old European Neanderthal

An international team of scientists has successfully extracted and sequenced the mitochondrial DNA from an 80,000-year-old adult Neanderthal tooth found in a small cave in Poland.

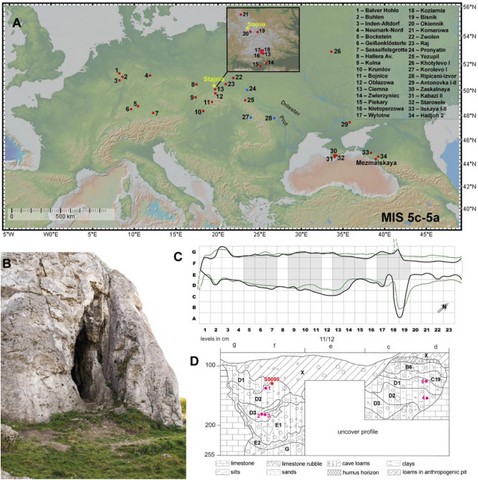

The Neanderthal molar tooth, dubbed S5000, was found in 2007 in Stajnia Cave in Poland’s Kraków-Częstochowa Upland.

An assemblage of stone tools and animal bones was recovered from the same archaeological layer, dated to marine isotope stage (MIS) 5a, between 82,000 and 71,000 years ago.

The finds were attributed to the Micoquian cultural tradition, which is documented in a vast area from the Saône River to the western shore of the Caspian Sea.

“The Stajnia S5000 molar is truly an exceptional find that sheds light on the debate over the wide distribution of the Micoquian artifacts,” said lead author Dr. Andrea Picin, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“The morphology of the tooth is typical of Neanderthal,” added co-author Dr. Stefano Benazzi, a paleoanthropologist at Bologna University. “The worn condition of the crown suggests that it belonged to an adult.”

3D digital model of the Stajnia S5000 molar. Image credit: Stefano Benazzi.

The analysis of the S5000 mitochondrial genome confirmed that the tooth dates to the MIS 5a period, making the oldest Neanderthal fossil found thus far in Central-Eastern Europe.

“The molecular age of approximately 80,000 years places the tooth from Stajnia Cave in this important period of Neanderthal history when the environment was characterized by extreme seasonality and some groups dispersed eastwards to Central Asia,” the researchers said.

“We were thrilled when the genetic analysis revealed that the tooth was at least 80,000 years old,” said co-authors Dr. Wioletta Nowaczewska from Wroclaw University and Dr. Adam Nadachowski from the Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals at the Polish Academy of Sciences.

“Fossils of this age are very difficult to find and, generally, DNA is not well preserved.” “At the beginning, we thought that the tooth was younger since it was found in an upper layer,” they said. “We were aware that Stajnia Cave is a complex site, and post-depositional frost disturbance mixed artifacts between layers. We are happily surprised by the result.”

Lithic artifacts from Stajnia Cave: (1-3) bifacial tool, (4, 5) preform of bifacial tool, (6, 7, 10) Levallois recurrent unidirectional flake, (8) fragment of bifacial tool, (11-12) scraper, (13) exhausted discoid core, (9) Levallois recurrent centripetal flakes, (14) discoid core. (Image credit: Picin et al, doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71504-x.)

“We were aware of the geographical importance of this tooth for adding more chronological points in the distribution map of genetic information of Neanderthals,” said co-author Dr. Mateja Hajdinjak, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“Poland, located at the crossroad between the Western European Plains and the Urals, is a key region in understanding these migrations and for solving questions about the adaptability and biology of Neanderthals in periglacial habitat,” Dr. Picin said.

The findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

_____

A. Picin et al. 2020. New perspectives on Neanderthal dispersal and turnover from Stajnia Cave (Poland). Sci Rep 10, 14778; doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71504-x

Enrico de Lazaro

Original article in sci-news.com

The Micoquian is the broadest and longest enduring cultural facies of the Late Middle Palaeolithic that spread across the periglacial and boreal environments of Europe between Eastern France, Poland, and Northern Caucasus. The mtDNA genome of Stajnia S5000 dates to MIS 5a making the tooth the oldest Neanderthal specimen from Central-Eastern Europe. Furthermore, S5000 mtDNA has the fewest number of differences to mtDNA of Mezmaiskaya 1 Neanderthal from Northern Caucasus, and is more distant from almost contemporaneous Neanderthals of Scladina and Hohlenstein-Stadel. This observation and the technological affinity between Poland and the Northern Caucasus could be the result of increased mobility of Neanderthals that changed their subsistence strategy for coping with the new low biomass environments and the increased foraging radius of gregarious animals. The Prut and Dniester rivers were probably used as the main corridors of dispersal. The persistence of the Micoquian techno-complex in South-Eastern Europe infers that this axis of mobility was also used at the beginning of MIS 3 when a Neanderthal population turnover occurred in the Northern Caucasus.

Researchers Sequence Genome of Neanderthal Woman from Chagyrskaya Cave

An international team of researchers has sequenced and analyzed the genome of an 80,000-year-old Neanderthal woman from Chagyrskaya Cave in the Altai Mountains, Siberia. The genome provides insights into Neanderthal population structure and history and allows the identification of genomic features unique to these human cousins.

Neanderthals and Denisovans are the closest evolutionary relatives of modern humans. Analyses of their genomes showed that they contributed genetically to present-day people outside sub-Saharan Africa.

However, the genomes of only two Neanderthals and one Denisovan have been sequenced to high quality.

One of these Neanderthal genomes was from an individual (Vindija 33) found in Vindija Cave in Croatia, whereas the other Neanderthal genome (Denisova 5 or the Altai Neanderthal) and the Denisovan genome (Denisova 3) both came from specimens discovered in Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains.

In the new research, Dr. Fabrizio Mafessoni from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and colleagues sequenced the genome from a Neanderthal phalanx (Chagyrskaya 8) found in 2011 at Chagyrskaya Cave, which is located about 100 km away from Denisova Cave. The researchers found that Chagyrskaya 8 lived 80,000 years ago, about 30,000 years after the Denisova 5 Neanderthal and 30,000 years before the Vindija 33 Neanderthal.

They also found that the Chagyrskaya Neanderthal was a female and that she was more closely related to Vindija 33 and other Neanderthals in western Eurasia than to Denisova 5 who lived earlier in the Altai Mountains.

“Chagyrskaya 8 is thus related to Neanderthal populations that moved east sometime between 120,000 and 80,000 years ago,” they said. “Interestingly, the artifacts found in Chagyrskaya Cave show similarities to artifact collections in central and eastern Europe, suggesting that Neanderthal populations coming from western Eurasia to Siberia may have brought their material culture with them.” “Some of these incoming Neanderthals encountered local Denisovan populations, as shown by Denisova 11, who had a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother related to the population in which Chagyrskaya 8 lived.”

From the variation in the genome, the authors estimated that Chagyrskaya 8 and other Siberian Neanderthals lived in relatively isolated populations of less than 60 individuals. In contrast, a Neanderthal from Europe, a Denisovan from the Altai Mountains, and ancient modern humans seem to have lived in populations of larger sizes.

When the team analyzed the Chagyrskaya 8 genome together with two previously sequenced Neanderthal genomes, they found that genes expressed in a part of the brain called striatum may have changed especially much, suggesting that the striatum may have evolved unique functions in Neanderthals.

“We found that genes expressed in the striatum during adolescence showed more changes that altered the resulting amino acid when compared to other areas of the brain,” Dr. Mafessoni said. “The results suggest that the striatum — a part of the brain which coordinates various aspects of cognition, including planning, decision-making, motivation and reward perception — may have played a unique role in Neanderthals.”

The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Fabrizio Mafessoni et al. A high-coverage Neandertal genome from Chagyrskaya Cave. PNAS, published online June 16, 2020; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004944117

Enrico de Lazaro, original article in sci-news.com

Women with Neanderthal Progesterone Gene Have Higher Fertility

A hormone called progesterone is important for preparing the uterine lining for egg implantation and in maintaining the early stages of pregnancy. Almost one in three women with European descent inherited a genetic variant of the progesterone receptor called V660L from Neanderthals. According to a new study, its carriers have higher fertility, more siblings, fewer miscarriages, and less bleeding during early pregnancy.

Progesterone is a steroid sex hormone produced by the ovaries, placenta, and adrenal glands that is involved in pregnancy, menstrual cycle, libido and embryogenesis in placental mammals. The progesterone receptor is encoded by the PGR gene on chromosome 11, and is most highly expressed in the endometrium.

“The progesterone receptor is an example of how favorable genetic variants that were introduced into modern humans by mixing with Neanderthals can have effects in people living today,” said study first author Dr. Hugo Zeberg, a researcher in the Department of Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

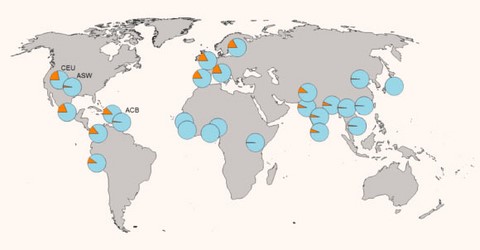

In the study, Dr. Zeberg and colleagues analyzed data from the UK Biobank cohort involving 452,264 Britons with European descent. They found that almost one in three women inherited the V660L variant from Neanderthals.

About 29% of them carry one copy of the Neanderthal receptor and 3% have two copies.

Allele frequency of V660L in 26 populations: the African American populations (ASW: African Ancestry in Southwest US, ACB: African Caribbeans in Barbados) have a lower frequency of V660L, similar to that in African populations, whereas North Americans with European ancestry (e.g., CEU: Utah Residents with Northern and Western European Ancestry) have frequency similar to European populations. Image credit: Zeberg et al, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa119.

“The proportion of women who inherited this gene is about 10 times greater than for most Neanderthal gene variants,” Dr. Zeberg said.“These findings suggest that the Neanderthal variant of the receptor has a favorable effect on fertility.”

“Our study shows that women who carry the Neanderthal variant of the receptor tend to have fewer bleedings during early pregnancy, fewer miscarriages, and give birth to more children,” the researchers said. “Molecular analyses revealed that these women produce more progesterone receptors in their cells, which may lead to increased sensitivity to progesterone and protection against early miscarriages and bleeding.”

The findings were published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution. Hugo Zeberg et al. The Neandertal Progesterone Receptor. Molecular Biology and Evolution, published online May 21, 2020; doi: 10.1093

Enrico de Lazaro, original article in sci-news.com

New Research sheds light on weaning of Neanderthals

A new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that the modern human nursing strategy, with onset of weaning at 5 to 6 months, was present among Neanderthals who lived between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago in what is now Italy.

The extent to which Neanderthals differ from Homo sapiens is the focus of many studies in human evolution.

There is debate about their pace of growth and early-life metabolic constraints, both of which are still poorly understood.

“The beginning of weaning relates to physiology rather than to cultural factors,” said co-first author Dr. Alessia Nava, a researcher in the Department of Maxillo-Facial Sciences at Sapienza University of Rome and the Skeletal Biology Research Centre at the University of Kent. “In modern humans, in fact, the first introduction of solid food occurs at around 6 months of age when the child needs a more energetic food supply, and it is shared by very different cultures and societies.” “Now, we know that also Neanderthals started to wean their children when modern humans do.”

“In particular, compared to other primates, it is highly conceivable that the high energy demand of the growing human brain triggers the early introduction of solid foods in child diet,” said co-first author Dr. Federico Lugli, a researcher at the University of Bologna.

In the study, the scientists analyzed an unprecedented set of fossil teeth from archaeological sites in northeastern Italy.

These four milk teeth include three Neanderthals, dated to between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago, and one Early Upper Paleolithic modern human as a comparative specimen.

“Our results imply similar energy demands during early infancy and a close pace of growth between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals,” said co-senior author Dr. Stefano Benazzi, a researcher in the Department of Cultural Heritage at the University of Bologna and the Department of Human Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “Taken together, these factors possibly suggest that Neanderthal newborns were of similar weight to modern human neonates, pointing to a likely similar gestational history and early-life ontogeny, and potentially shorter inter-birth interval.”

Using time-resolved strontium isotope analyses, the authors also collected data on the regional mobility of the Neanderthals.

“Neanderthals were less mobile than previously suggested by other scientists,” said co-senior author Dr. Wolfgang Müller, a researcher in the Institute of Geosciences and the Frankfurt Isotope and Element Research Center at Goethe University Frankfurt. “The strontium isotope signature registered in their teeth indicates in fact that they have spent most of the time close to their home.” “This reflects a very modern mental template and a likely thoughtful use of local resources.”

“Despite the general cooling during the period of interest, northeastern Italy has almost always been a place rich in food, ecological variability and caves, ultimately explaining the survival of Neanderthals in this region till about 45,000 years ago,” said co-senior author Dr. Marco Peresani, a researcher in the Institute of Environmental Geology and Geoengineering-IGAG CNR and the Department of Humanities at the University of Ferrara.

_____

Alessia Nava et al. Early life of Neanderthals. PNAS, published online November 2, 2020; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2011765117

This article is from sci-news.com

Neanderthals’ Deep and Short Ribcage was Already Present at Birth

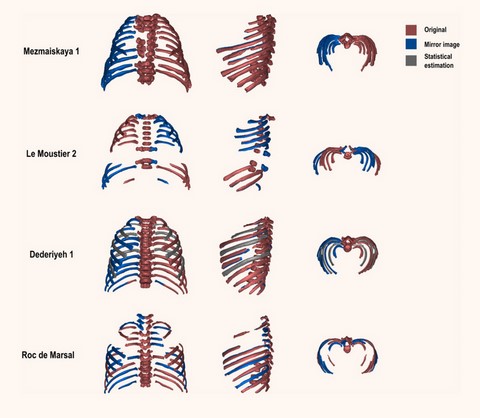

An international team of researchers has virtually reconstructed the ribcages of four Neanderthal individuals from birth to around 3 years old and found that most of the skeletal differences between the Neanderthal and modern human ribcage are already largely established at birth, the Neanderthal ribcage being deeper and shorter than that of modern humans.

“Despite genetic similarities that allowed for admixture between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans, there is a well-established consensus that Neanderthals showed significant morphological differences when compared to humans,” said Dr. Daniel García-Martínez from the University of Bordeaux, Spain’s Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, and the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana, and colleagues. “Some of these differences are inherited traits from their Pleistocene ancestors, while others are present exclusively in Neanderthals.”

“Neanderthals were highly encephalized and heavy-bodied hominins requiring large amounts of energy.” “It has been proposed that to fulfill these energetic demands, their ribcage had a large estimated total lung capacity and a different shape that included a shorter, slightly deeper, and larger chest, compared to modern humans.”

Virtual reconstruction of the four Neanderthal individuals studied by García-Martínez et al.; bones that are preserved in the original specimen are shown in red, whereas mirror images are shown in blue and statistical estimations in gray. Image credit: García-Martínez et al., doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb4377.

To identify potential differences with modern humans in ribcage morphology, the researchers used virtual and statistical methods to reconstruct the ribcage of four young Neanderthals.

Specifically, they reconstructed the ribcages of perinatal individuals of Mezmaiskaya 1 (7 to 14 days old) and Le Moustier 2 (less than 120 days) and infant individuals from Dederiyeh 1 (1.41 years) and Roc de Marsal (2.54 years).

The most complete Neanderthal specimen, Dederiyeh 1, revealed the species had relatively longer mid-thoracic ribs compared to its uppermost and lowermost ribs and a spine folded inward toward the center of the body, forming a cavity on the outside of the back.

The scientists compared ribcage development in these specimens with a baseline for modern human development in the first three years of life, which they derived from a forensic assessment of remains from 29 humans.

The Neanderthal specimens had consistently shorter spines and deeper ribcages.

“The bulky Neanderthal ribcage may have been genetically inherited, at least in part, from early Pleistocene ancestors,” the authors concluded.

Their paper was published in the journal Science Advances. Daniel García-Martínez et al. 2020. Early development of the Neanderthal ribcage reveals a different body shape at birth compared to modern humans. Science Advances 6 (41): eabb4377; doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb4377