Neanderthal string

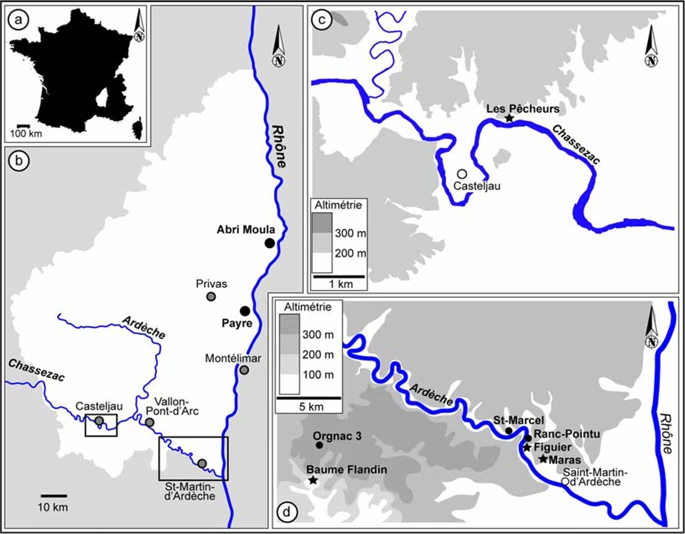

Now, in the Abri-du-Maras, in France, a 40,000 to 50,000 year-old piece of "string" attributable to the Neanderthal has been discovered...

Oldest known string upends assumptions on Neanderthal intelligence

Archaeologists discover 40-50,000-year-old cord in France, suggesting ancient hominids had some understanding of numbers, use of tree fibers

By Malcolm Ritter 13 April 2020, 2:55 am The Times of Israel.

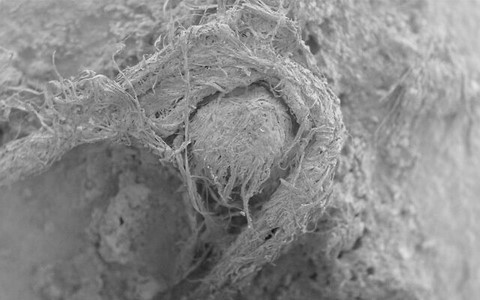

It looked like a white splotch on the underside of a Neanderthal stone tool, but a microscope showed it was a bunch of fibers twisted around each other.

Further examination revealed it was the first direct evidence that Neanderthals could make string, and the oldest known direct evidence for string-making overall, researchers say.

The find implies our evolutionary cousins had some understanding of numbers and the trees that furnished the raw material, they say. It’s the latest discovery to show Neanderthals were smarter than modern-day people often assume.

Bruce Hardy, of Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, and colleagues reported the discovery in a paper released Thursday by the journal Scientific Reports. The string hints at the possibility of other Neanderthal abilities, like making bags, mats, nets and fabric, they said.

The string came from an archaeological site in the Rhone River valley of southeastern France, and is roughly 40,000 to 50,000 years old. Researchers don’t know how Neanderthals used the string or even whether it had been originally attached to the stone cutting tool.

Maybe the tool happened to fall on top of the string, preserving the quarter-inch (6.2 mm) segment while the rest disintegrated over time, Hardy said. The string is about one-fiftieth of an inch (0.55 mm) wide.

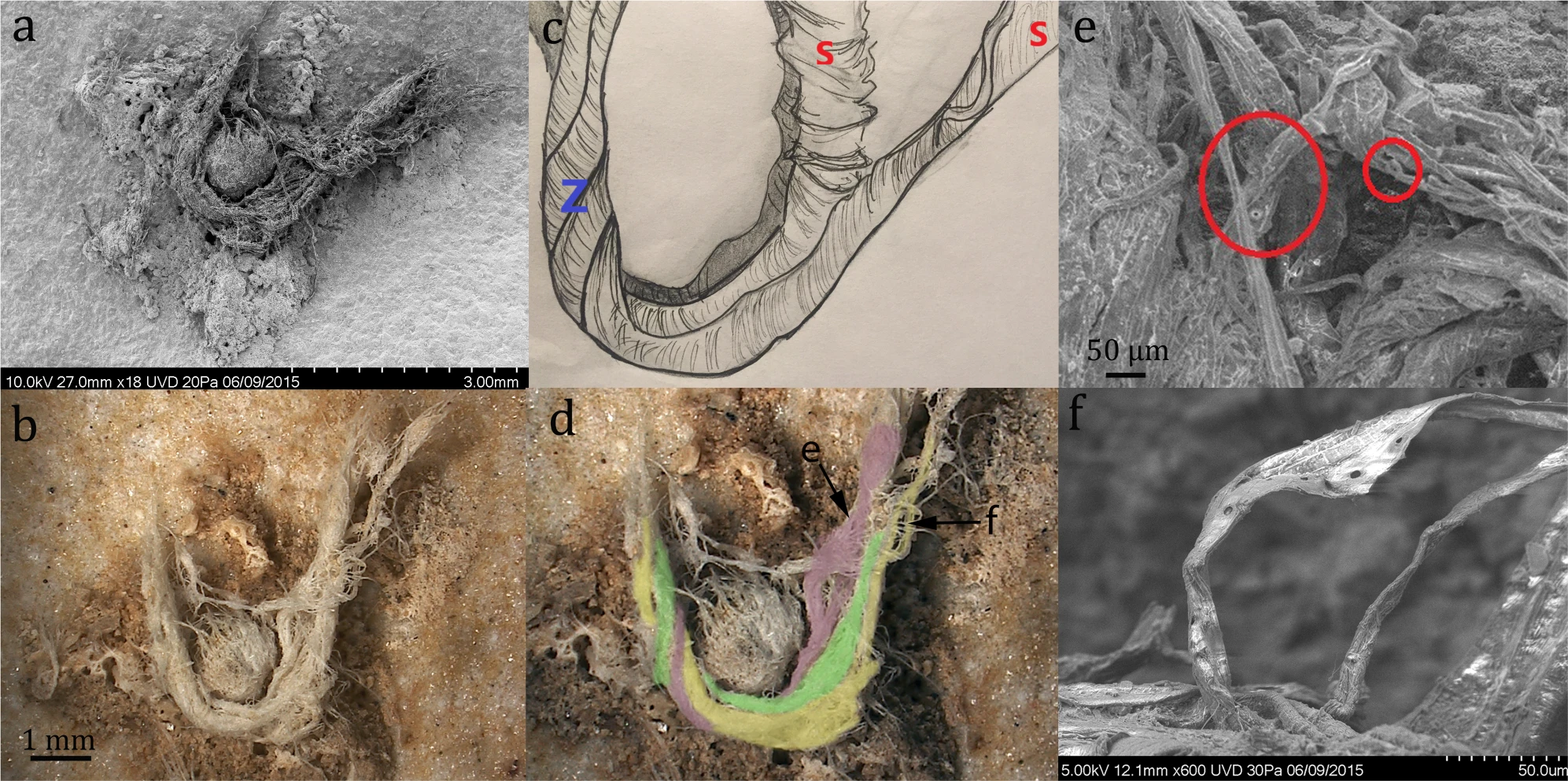

It was made of fiber from the inner bark of trees. Neanderthals twisted three bundles of fibers together counterclockwise, and then twisted these bundles together clockwise to make the string. That assembly process shows some sense of numbers, Hardy said.

Paola Villa, a Neanderthal expert at the University of Colorado Museum who was not involved in the new study, noted that Hardy had previously found “tantalizing evidence” for string-making by Neanderthals. The new work now illustrates the ability directly, she said.

From the article in Nature:

The cord is not necessarily related to the use of the tool. Its presence on the inferior surface of the flake during excavation demonstrates that it was deposited before or contemporaneous with the flake. If it was contemporaneous with the deposition of the flake, it could have been wrapped around it as part of a haft or could even have been part of a net or bag. Previous analysis of impact fractures on artefacts from the site suggests the use of hafting and provide potential support for this possibility. If it was deposited before the flake, it could represent a number of different items but nonetheless illustrates the use of fibre technology at the site.

(a) SEM photo of cord fragment, (b) 3D Hirox photo of cord fragment, (c) schematic drawing illustrating s and Z twist; (d) enlarged Hirox photo with cord structure highlighted, arrows indicate location of photos e and f; (e) SEM photo of bordered pits (circled in red); (f) SEM photo of bordered pits. (Drawing by C. Kerfant; Hirox: C2RMF, N. Mélard).

Other early indirect evidence of fibre technology is impressions on fired clay from Gravettian sites in Moravia as early as 28 ka3. These impressions reveal weaving technology and the production of textiles. The complexity of the textiles suggests that they are part of a well-established tradition that began much earlier.

In terms of the actual preservation of fibre technology, the Upper Paleolithic waterlogged site of Ohalo II yielded three fragments of fibres with a Z twist approximately -19,000. Remnants of a 6-ply cord were found at Lascaux and date to approximately -17,000. The cord fragment from Abri du Maras is older still, dating to between 41,000 and 52,000.

Thus, it appears increasingly likely that fibre technology is much older than previously thought.

While it is clear that the cord from Abri du Maras demonstrates Neanderthals’ ability to manufacture cordage, it hints at a much larger fibre technology. Once the production of a twisted, plied cord has been accomplished it is possible to manufacture bags, mats, nets, fabric, baskets, structures, snares, and even watercraft. The cord from Abri du Maras consists of fibres derived from the inner bark of gymnosperms, likely conifers. The fibrous layer of the inner bark is referred to as bast and eventually hardens to form bark. In order to make cordage, Neanderthals had extensive knowledge of the growth and seasonality of these trees. Bast fibres are easier to separate from the bark and the underlying wood in early spring as the sap begins to rise. The fibres increase in size and thickness as growth continues. The best times for harvesting bast fibres would be from early spring to early summer. Once bark is removed from the tree, beating can help separate the bast fibres from the bark. Additionally, retting the fibres by soaking in water aids in their separation and can soften and improve the quality of the bast. The bast must then be separated into strands and can be twisted into cordage. In this case, three groups of fibres were separated and twisted clockwise (s-twist). Once twisted the strands were twined counterclockwise (Z-twist) to form a cord.

Ropes and baskets are central to a large number of human activities. They facilitate the transport and storage of foodstuffs, aid in the design of complex tools (hafts, fishing, navigation) or objects (art, decoration). The technological and artistic applications of twisted fibre technologies are vast. Once adopted, fibre technology would have been indispensable and would have been a part of everyday life. In reconstructing land use patterns, paleoanthropologists typically give priority to activities such as hunting and acquiring lithic raw material. Fibre acquisition, processing, and production may have also played an important role in scheduling daily and seasonal activities. String and rope manufacture are time intensive activities and large amounts of string are required for the production of carrying objects such as bags. In an ethnomathematical study of the Maya, Chahine found that a 1.3 foot Maguey bag required over 400 meters of cordage.

Thinking of the environment as including both natural and anthropogenic objects makes it possible to ask several questions about the choices made by cultural groups. Topography, climate, and distribution of plant and animal species are all key factors to consider. Plants play an important role not only in the material conception of objects but also in the formation of the thought of a culture, its representation of the world and its cosmogony.

Overall, cordage manufacture has a complex chaîne operatoire. Although wooden artefacts are rare, other finds attest to Neanderthals detailed knowledge of trees. They chose boxwood for its density and used fire in the production of “digging sticks” at Poggetti Vecchi approximately -175,000. In the construction of the Schöningen spears, they decentered the point to increase strength. Furthermore, Neanderthals were manufacturing birch bark tar in the Middle Pleistocene of Italy and at the sites of Konigsaue and Inden-Altdorf in Germany. Based on this evidence, the utilization of bast fibres from trees is an obvious outcome of their intimate arboreal knowledge. While some have suggested that cordage manufacture may have been a gendered activity, we feel our current evidence is inadequate to address that question.

Understanding archaeological finds in terms of taskscapes, locating socially-situated tasks in the landscape, allows us to more fully appreciate the complexity of Neanderthal technology and social life. The production of cordage is complex and requires detailed knowledge of plants, seasonality, planning, retting, etc. Indeed, the production of cordage requires an understanding of mathematical concepts and general numeracy in the creation of sets of elements and pairs of numbers to create a structure. Indeed, numerosity has been suggested as “one possible feral cognitive basis for abstraction and modern symbolic thinking.” Malafouris has suggested that a material instantiation of number concepts was necessary for the emergence of cognitive numerical ability. The production of cordage, with its use of pairs and sets, may represent one such instantiation. The production of the cord from Abri du Maras requires keeping track of multiple, sequential operations simultaneously. These are not just an iterative sequence of steps because each has to have access to the previous stages. The bast fibres are first s-twisted to form yarn, then the yarns z-twisted (in the opposite direction to prevent unravelling) to form a strand or cord. Cordage production entails context sensitive operational memory to keep track of each operation. As the structure becomes more complex (multiple cords twisted to form a rope, ropes interlaced to form knots), it demonstrates an “infinite use of finite means” and requires a cognitive complexity similar to that required by human language.

The cord fragment from Abri du Maras is the oldest direct evidence of fibre technology to date. Its production demonstrates a detailed ecological understanding of trees and how to transform them into entirely different functional substances. Fibre technology would have been an important part of everyday life and would have influenced seasonal scheduling and mobility. Furthermore, the production of cordage implies a cognitive understanding of numeracy and context sensitive operational memory. Given the ongoing revelations of Neanderthal art and technology, it is difficult to see how we can regard Neanderthals as anything other than the cognitive equals of modern humans.